The (West's) Obsession to Classify Things: A Philosophical Investigation in Beliefs

The unknown is terrifying. Knowing is linked to security, for the simple reason that if you know nothing will "come out of the blue", there is nothing to fear. The idiom paints a pretty image we can use: that of the ocean. If you are dropped into the ocean, no matter how good a swimmer you are, there will always be the nagging fear of "what is below me?". This is because we cannot see or know what is underneath us. The Western mind cannot accept this fear of the unknown, therefore it wants to classify and know everything: when no stone is left unturned, there will be nothing fear-inducing left. But this obsession to classify everything, in effect, causes a pain so bad that it will destroy the little well-being left in the West. My main thesis in this post is the following: classifying everything to enhance our knowledge (in order to get away from the unknown, i.e. sources of pain) inadvertently causes a great unknown that cannot be bridged.

Language Inherently Classifies

The world is not made up out of brute facts. The world is, in fact, not made out of anything. This is because once you start to think about "the world is made out of x" you start to classify. It is said that language originated by the first grunt for food: everything "grunt" was food, everything non-"grunt" was not food. This seems like a project that is deemed to fail from the start: how can you use something (language) which inherently classifies things to describe this obsession of describing things in order to show how it leads to classifying something that cannot be classified? In other words, if language inherently classifies things, how can we even begin to understand how things are if they are not classified?

Let us first ask, is this attitude correct? Is language inherently classifying? An example will help. "The tree over there." How does this sentence even get meaning? How does the reader know what the sentence means? There is a myriad of answers produced by as many thinkers, but simply put, I think, the correct answer is simply that words get their meaning negatively; in other words, from not being this or that. The tree is not the road or that bush or that animal. "Over there" is not over here or over there (i.e. opposite position). The sentence has meaning because it is not another sentence. The sentence, in a sense, occupies a certain space, a space with meaning. That meaning can be changed etc., but in a system, it occupies a certain meaning.

What does this mean? It means that there cannot be meaning without classifying things. You are either positive (i.e. the object) or negative (i.e. not the object). Reiterating: the first grunt for food classified the world into "food" or "not-food".

Beliefs and Classification

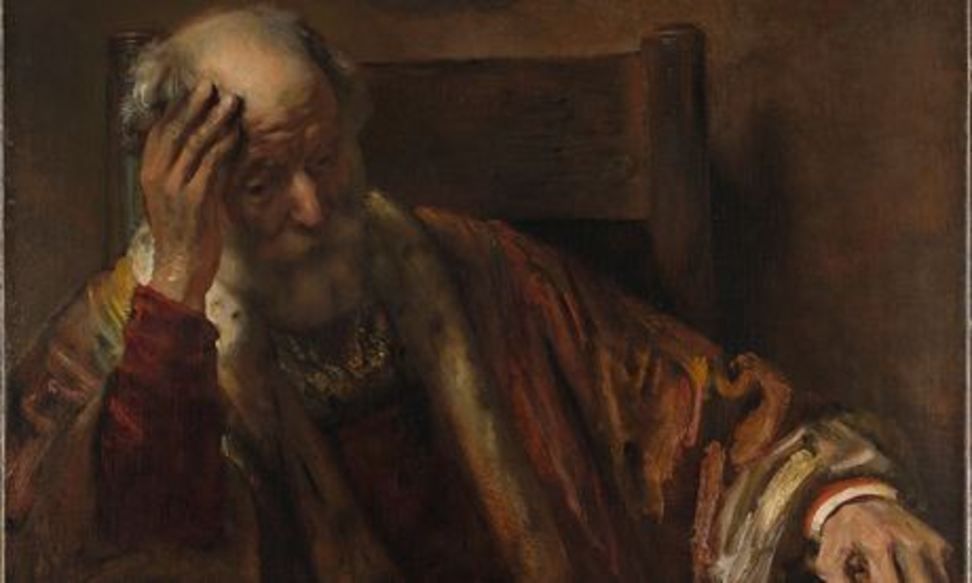

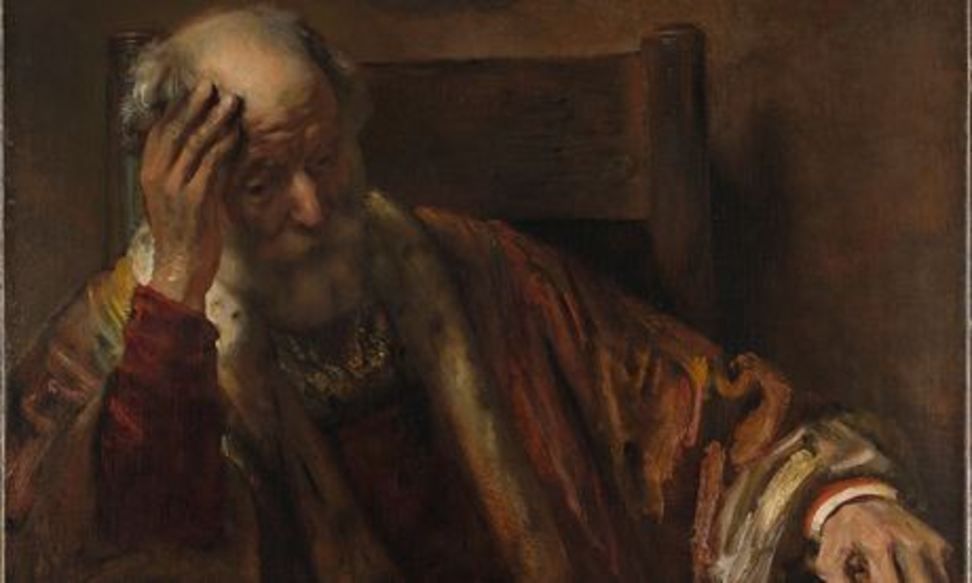

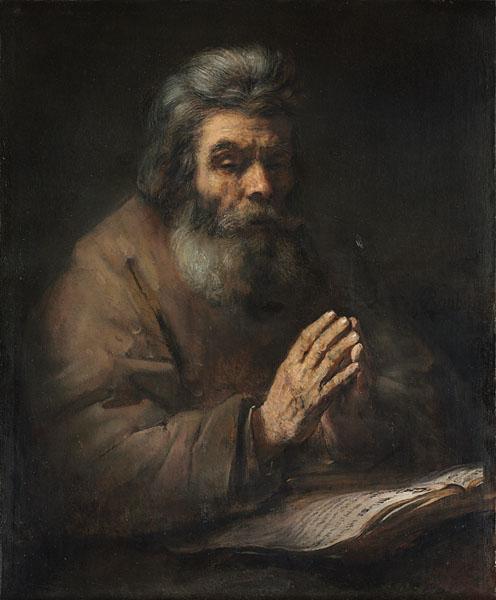

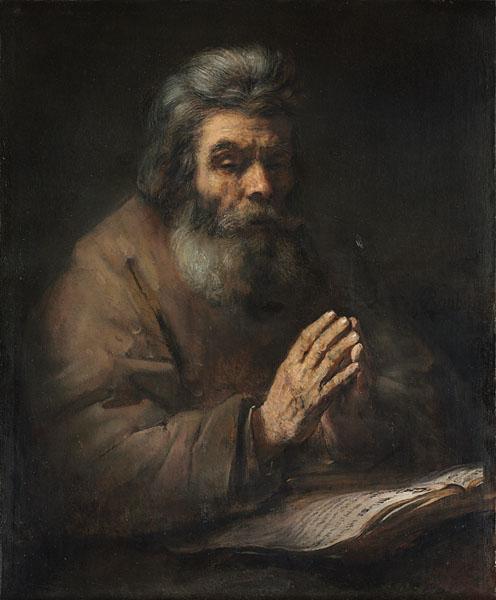

The inherent nature of classifying something is that it structures something binarily as good or bad. It is done without knowledge. The very nature of classifying can be understood as knowable is good and classifiable, unknowable is bad because it cannot be classified. It is said that Socrates took this position of unclassifiable: he was no mere man, but he was no god either. This unclassifiable nature in the end meant his death: people, or the system, cannot handle the unknown, or that which cannot be classified. Nietzsche also tells us that: "Wherever there have been powerful societies, governments, religions, or public opinions -- in short, wherever there was any kind of tyranny, it has hated the lonely philosopher; for philosophy opens up a refuge for man where no tyranny can reach: the cave of inwardness, the labyrinth of the breast; and that annoys all tyrants."

This inwardness cannot be regulated. Once again the hierarchical structure is created: that between the classifiable and regulatable. An inherent structure is apparent: that which can be regulated equals good and that which cannot, equals bad (because it induces fear and brings back the unknown, that which the West hates most). The most unclassifiable is the true philosopher: the person who does not get motivated or swayed by beliefs. What are beliefs? Why are they negative? And why is this important for society today?

Rejecting Beliefs: The Philosopher of Modern Times as an Unclassifiable Unknown

Dogma, or belief, can be seen as that which one thinks is true, or simply that of popular opinion. When one sides with what is unpopular, i.e. Socratic gadfly, questioning everything, can get one killed. The philosopher is thus someone who does not accept dogma, or beliefs, because beliefs are something which is inherently unknowable and thus dangerous. Why is this dangerous? It is dangerous for the simple reason that it can be used to sway the unphilosophical into believing something which is false, but aligns with the popular opinion. The philosopher rejects this, but this in a way makes him or her unclassifiable, and thus dangerous because he or she is not good or bad. The West cannot deal with this ambiguity.

Why do I say this? Take for example the Western dilemma of right against left. There is no middle ground, the middle ground is a mythical position that induces fear in both sides. It is easier to classify and box people into a neat category on the opposite side of the debate, even if that person does not fit into the neat box. The fear of the unknown and unclassifiable forces the other side to lump all that cannot be understood into the same box. This works both sides of the debate. The middle ground is an unoccupiable space; until the philosopher steps in.

Let us quickly look at the main thesis mentioned at the outset: classifying everything inadvertently causes a great unknown that cannot be bridged. This is the middle ground, a great unknown that cannot be bridged, an unoccupiable space. Can this gap be bridged? The philosopher takes up this space as an unclassifiable agent: someone who rejects beliefs, i.e. popular opinion, he does not choose sides. This leads to a paradox: the right or left, the sides of an argument, the rifts created by classifying, does not acknowledge the philosopher, because the middle ground doesn't exist, or it is not occupiable. Will the philosopher's words only be a vain attempt at shouting into the abyss?

An Attempt to Answer the Unanswerable

A vain shout into the abyss, a call that will never be answered, a road that leads to nowhere. The philosopher occupies the unoccupiable, shouting into the abyss until his or her own breakdown. Socrates was killed because he occupied this space, today we are not killed, but ridiculed into silence. Silence for the philosopher is like death. Trying to answer this will lead to nothing. Let us contemplate the thesis for a last time: classifying everything inadvertently causes a great unknown that cannot be bridged. In classifying everything, with the aim of taking away the fear of the other, the classifying created a unknown space that induces fear into those who wanted to get away from the fear. In other words, by classifying, they created the philosopher, they created what they wanted to kill so dearly.

Comments