Philosophy 101: How might I live? Part 3: Plato's Forms as Concepts

Introduction: Socrates and Plato

Socrates, through the mouthpiece of Plato proclaimed to know only one thing: that he knows nothing. He did not see himself as wise, however, he was wise in not proclaiming to know things which he cannot know. That turned out to be most things. But first, who is Socrates and Plato, why are they discussed here, and how does this discussion influence our question of how might I live?

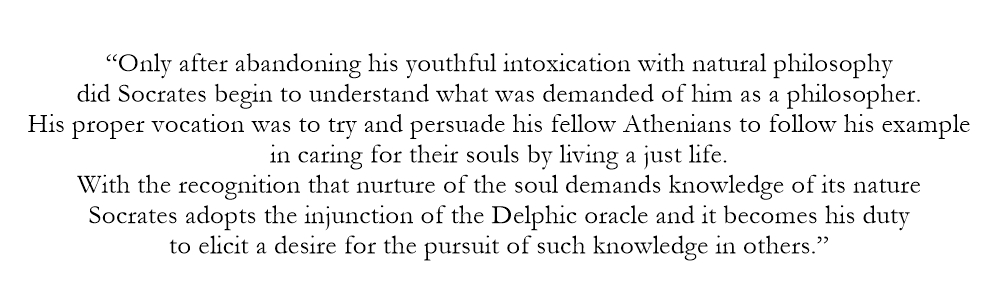

Like so many other influential thinkers, Socrates did not write anything down. Plato, one of his students, recorded the words of Socrates. Socrates thus becomes an illusive figure, who was he really? No one really knows. We only have accounts of Socrates, like the Platonic account of Socrates. That being said, we can learn a lot from these figures. The question of how might I live is greatly influenced by the Socratic dictum of an unexamined life is not worth living. So, let us proceed to uncover some of the wisdom in these figures.

Platonic Forms and the Cave Allegory

How do we know anything? This is the question we started with in the previous essay. This is the same question Plato asks. His answer is, in simplified terms, that we are born with innate memories of the forms. We should thus remember what is already innate to us. This is often called “anamnesis”, which basically means that “learning” things consist of “remembering” to what we (before our birth) were previously exposed to. Where does this innate knowledge come from? Or in other words, where do we gain this knowledge? In the realm of forms. Let us take a step back, how did Plato get to this and what are the implications?

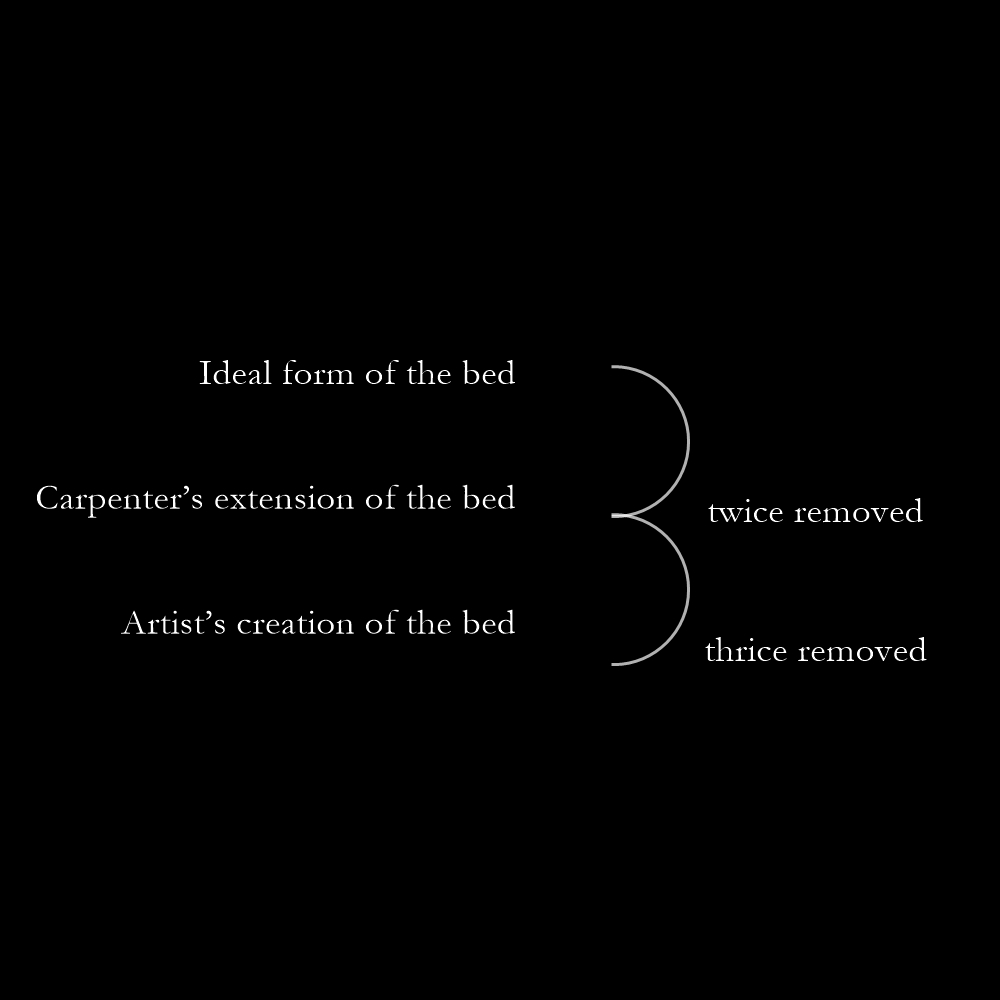

Anamnesis forms part of Plato’s “epistemology”. Simply put, epistemology is someone’s attempt to answer the question “How do we know something?”. As we saw, Plato states that we remember what is innate when we learn. These “ideas” or “forms” form part of what philosophers call the realm of forms. Before birth, our “soul” is exposed to these ideas, but when we are born, we forget these forms. The world out there, consists out of things which are imperfect copies of those things in the realm of forms. Plato, through Socrates, describes this when he critiques the artist who deceives people with his or her art. Take the idea of a bed. In the realm of forms, there exists the ideal form of a bed. The carpenter, through learning – in other words, remembering – copies from the realm of ideas a bed which he then makes. The carpenter’s bed is, according to this theory, twice removed from the “perfect” or “ideal” bed. When the artist copies the bed onto a painting, it is thricely removed from the “ideal” bed in the realm of ideas. See the image below:

Why is this important and relevant for us today? I think the importance of this theory is illustrated when we analyse Socrates’ cave allegory. Socrates asks us to imagine a series of prisoners who are bound in such a way so that they can only look at a wall in front of them. On this wall, shadows are projected from people walking over a bridge. A flame is in-between the prisoners and those who cast the shadow. The prisoners cannot see who or what creates the shadow, so the shadows in turn simply is the prisoners’ reality. One day a prisoner breaks free and sees that the shadows are created by people walking with figures on their heads. These are already twice removed from the true forms; the prisoners’ reality is thus based on thrice removed shadows. Once outside, the prisoner sees reality or the “real real”, or things in themselves. The prisoner, with this new knowledge, goes down to the other prisoners to inform them that their reality of the shadows on the wall is thrice removed form the actual world. Subsequently, the liberated prisoner is killed because this is too foreign to the prisoners, it would disrupt their security.

Education as Liberation

Should we all strive to be the liberated prisoner and be killed by those who are not liberated? This is a tough question. Let us take stock before we attempt to analyse this. Innately we have knowledge, by learning we remember what we have forgotten. We are, before remembering, the prisoners tied up looking at the shadows in the wall. Once we remember, we see that our knowledge is incomplete and thrice removed. We need to escape the cave and learn about the real world. The sun in Socrates’ symbolizes the Good. This is important to understand the dictum of why an unexamined life is not worth living. When we remember through educating ourselves, we will live a good and happy life. The prisoners in the cave is not happy. Penelope Levitt (1981: 229) states this beautifully:

Philosophy as the love of wisdom is the only way in which we can examine our lives and accordingly live an examined life. This equates to educating oneself to escape Socrates’ cave. How might I live my life? By educating oneself to become liberated. We can only live a just life when we examine if constantly and never settle with knowledge as it is as those in the cave do. Should we attempt to persuade the other prisoners to join us? This will be next weeks topic.

Source/Further reading

Levitt, P. 1981. Plato's Conception of Philosophy, in Z. van Straaten (ed.) Basic Concepts in Philosophy. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

Comments