Philosophical Counselling: What is Philosophical Counselling and Philosophy?

Philosophical counselling has become a kind of a buzzword in counselling circles. Philosophical counselling (henceforth PC) is rarely spoken of in philosophical circles. This is somewhat a mystery. In science, for example, you get theoretical science and practical science. Philosophy is almost exclusively theoretical, except for some practical fields such as applied (practical) ethics. Philosophy today rarely leave the ivory tower. If one trace philosophy back to its (western) roots, a different picture arises. Philosophy was initially a way of life. It “demanded a radical conversion and transformation of [one’s] way of being” (Hadot 1999: 265). Philosophía (φιλοσοφία) is the love of wisdom. The love of wisdom as a way of life was intended to “bring peace of mind (ataraxia)” and to be “therapeutic, [intending] to cure mankind’s anguish” (Hadot 1999: 265-266). Philosophy today is rather “a discourse developed in the classroom, and then consigned to books, [and texts] which requires exegesis [or critical interpretation]” (Hadot 1999: 271). Philosophía went from an “art of living” to philosophy, the “construction of … technical jargon reserved for specialists” (Hadot 1999: 272). (This is not always the case, but more than often philosophy is not something you can practically use in everyday life. Are we brains in a vat? If we are what does it matter to everyday life? It can either cause mass uproars or it cause nothing, as is the case, I think.)

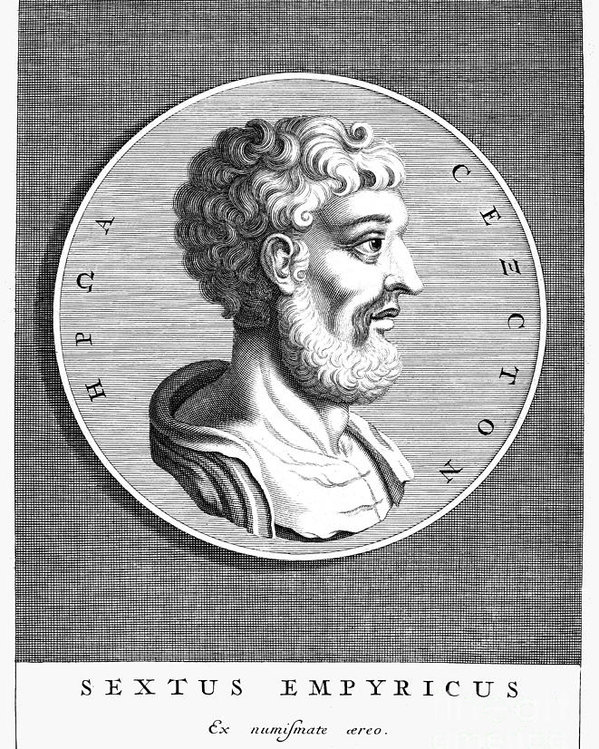

If we consider what PC is, it will be beneficial to understand what philosophy is. So, without further ado, what is philosophy? Some claim that philosophy is therapy. The idea of philosophy as therapy is not new. Sextus Empericus used Pyrrhonian scepticism to “cure by argument [the] rashness of the Dogmatist” (PH III.280). But this notion of philosophy as therapy is problematic. Firstly, it should not be a philosophical position, but an exercise in interpretation (Wisnewski 2003: 53). This simply means that one cannot use philosophy as therapy in the normal sense of therapy, it should rather be a “by-product” of philosophizing. This in a sense resonates with Socrates’ position as the midwife. The person undergoing PC has the wisdom inside of them, it is up to the philosophical counsellor to help with the birth of innate wisdom of the counselee. Secondly, the contemporary understanding of the word “therapy” entails a curing of some sort, which PC should not aim at, as mentioned above, a “cure” should only follow as a by-product and not something actively searched for. To take stock, philosophy should thus be used practically to help the counselee (client, visitor, dialogue partner) give birth to innate wisdom.

This answer still lacks what philosophy is. One can still ask “What is philosophy then?”. Marinoff (2003: 17) writes: “If you want to think clearly, you need to nourish your mind with the healthiest food available. That food is philosophy: great thought, as opposed to junk thought.” Defining philosophy is not easy, but there needs to be something concrete about it. A working definition of what philosophy is, can be put forward:

“Philosophy is a way of life that, when coupled with critical thinking and interpretation (hermeneutics), can lend itself to be a therapeutic experience that will extend and broaden worldviews in such a way to encourage self-understanding by placing fragmented pieces of life into a cohesive whole.”

(This definition still lacks a lot of things that can be added, it also doesn’t cover things like ontology etc. which has become “staple” philosophical content.)

So, what is PC then? This is also not something that can be answered. Some people claim it cannot be defined, some claim it should have a strict method, but there is no consensus on this issue. This can be problematic, but also productive, giving free rein to some creative minds. But the biggest concern about this lack of definition is when a potential client asks what is PC. If you cannot give an answer you will probably lose the client, and in the process hurt the name of PC. Some of the prominent figures in PC gave their interpretations of what PC should be, entail and present. Figures like Marinoff, Raabe, Lahav and Schuster will be discussed in more detail in forthcoming essays. The take away: between these four “pillar” figures in PC there is not much consensus.

This makes the task of explaining PC difficult. From the outset, I claimed, that PC should be defined in relation with what philosophy is. It is after all PHILOSOPHICAL counselling and not philosophical COUNSELLING. According to Raabe (2001: 203) PC is a “trained philosopher” who helps someone with a “problem”, and Lahav (1996: 277) states that the philosophical counsellor needs not only be a counsellor but a philosopher per se. Taking stock one can say, without much controversy, that a philosophical counsellor needs to be a philosopher. What is a philosopher? Someone who does philosophy. This brings us back to the question of what philosophy is.

One possible answer to this question of what philosophy is, is scepticism. Philosophy is the love of wisdom, but how does one get this love of wisdom? Through inquiry, or the root cause of scepticism: finding out the truth through all the claims being made about the truth. The original Greek term σκεπτικός (skeptikós) means to inquire, and the root σκέπτομαι (sképtomai) to consider things. Sextus Empericus in his Outlines of Pyrrhonism says that “Scepticism is an ability to set out oppositions among things” (PH I.8). The σκεπτικός (skeptikós) is someone “who looks or examines” and does not stop searching (PH I.1; Hankinson 1995: 12). Scepticism, or Pyrrhonism, for Sextus is thus the ability, when one investigates, to lay things out, to consider opposing views and to suspend judgement because of equipollence (PH 1, 9-10).

When one considers contemporary scepticism, it sometimes refers to those who claim that we cannot know with certainty, it is used to form thought experiments that lead to positions that are “unsustainable and astonishingly trivial”, and it is used synonymously with “doubt” (Frede 2006; Berry 2011: 7). Scepticism in this modern sense became an “empty but highly charged swear word” (Hallie as quoted by Groarke 1990: 3). On the one hand there is the ancient inquirer, and on the other hand the modern doubter.

This in a sense answers the question, but not sufficiently. In forthcoming essays I’d like to make a better attempt. For now, one can formulate a working definition of what PC is:

“PC is having a philosophical orientated dialogue with a trained and undogmatic professional philosopher about everyday problems in a language that the counselee will understand and with no aforementioned fixed goal, which the counselee can, in turn, take to heart to practice it as a way of life applying it where needed.”

The philosophical counsellor, on the other hand, needs to be an inquirer into things, loving the wisdom he/she gets from this inquiry and trying to help others who may struggle in life. This is still a work in progress, but this may be something that can help understanding this hopefully great new venture of bringing philosophy back to the people.

Further reading/sources

Berry, J.N. 2011. Nietzsche and the ancient skeptical tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frede, M. 2006. Scepticism, in C.F. Salazar (ed.). Brill's New Pauly: Encyclopaedia of the ancient world (online). Available: http://referenceworks.brillonline.com.ez.sun.ac.za/entries/brill-s-new-pauly/*-e12224950 [23 July 2018].

Groarke, L. 1990. Greek scepticism: Anti-realist trends in ancient thought. London: McGill-Queen's University Press.

Hadot, P. 1999. Philosophy as a way of life: Spiritual exercises from Socrates to Foucault. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hankinson, R.J. 1995. The Sceptics: The arguments of the philosophers. London: Routledge.

Lahav, R. 1996. What is philosophical in philosophical counselling?. Journal of Applied Philosophy, 13(3): 259-278.

Marinoff, L. 2003. The therapy for the sane. New York: Bloomsbury.

Raabe, P.B. 2001. Philosophical counseling: Theory and practice. London: Praeger.

Wisnewski, J.J. 2003. Five forms of philosophical therapy. Philosophy Today, 47(1): 53-79.

Comments